Laparoscopic Paraaortic Lymph Node Sampling in Gastric Cancer Patients with Suspected Paraaortic Lymph Node Metastasis

Article information

Abstract

D2 lymphadenectomy is the standard approach for lymph node dissection in curable gastric cancer. However, paraaortic lymph node (PALN) dissection in addition to D2 lymphadenectomy has not been shown to improve survival rates and is therefore not routinely performed. Nevertheless, PALN sampling may be indicated for diagnostic purposes because it can provide critical information for accurate staging and treatment planning. Laparoscopic PALN sampling, however, poses significant challenges due to limited accessibility and visibility in the paraaortic region. Moreover, the proximity of major blood vessels, such as the abdominal aorta and renal vein, is another difficult aspect of the procedure. In this context, we present two cases to demonstrate practical strategies for facilitating laparoscopic PALN sampling. The procedure can be effectively performed by first identifying the ligament of Treitz and then, when necessary, fixing the small bowel mesentery to the abdominal wall using a tagging suture so that there is adequate vision and enough working space. This enables careful and precise dissection of the target tissue without compromising the feasibility and safety of the operation.

Introduction

D2 lymphadenectomy is the standard approach in locally advanced gastric cancer [1,2]. Paraaortic lymph node (PALN), which are not included in the D2 lymphadenectomy, are anatomically categorized as 16a1, 16a2, 16b1, and 16b2 based on their intraperitoneal location [3,4]. The presence of PALN metastasis represents stage IV disease [3].

During the preoperative evaluation, cases suggestive of potential PALN metastasis occasionally arise. For patients not suspected of stage IV, the most reliable method to confirm PALN metastasis is through surgical sampling followed by histopathological evaluation. The results of such biopsies are crucial for accurate staging and determining the optimal treatment. However, PALN sampling is technically challenging due to the anatomical complexity and the difficulty in locating these nodes.

In this report, we share our experiences with laparoscopic PALN sampling in gastric cancer patients suspected of PALN metastasis, providing insights to facilitate this procedure in similar clinical scenarios.

Case Presentation

Case 1

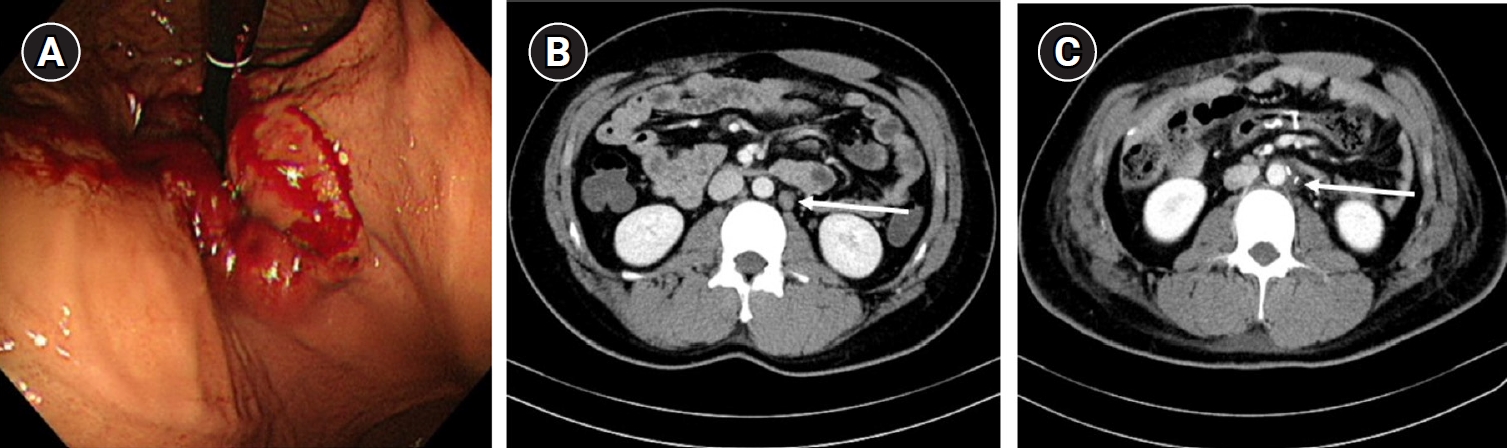

A 23-year-old male presented with dysphagia and underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and computed tomography (CT) 1 year prior to evaluation. He was diagnosed with gastroesophageal junction cancer exhibiting clinical serosal invasion and extensive lymph node metastasis, including suspected PALN involvement (Fig. 1A). The patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and subsequent CT imaging revealed a slight reduction in tumor extent but persistent left PALN enlargement (Fig. 1B).

(A) Esophagogastroduodenoscopy diagnosed with gastroesophageal junction cancer. (B) Computed tomography performed 4 months after the start of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Left paraaortic lymph node enlargement still remained (arrow). (C) Follow up computed tomography examined 4 months after the operation. The enlarged left paraaortic lymph node before the operation was resected and disappeared (arrow).

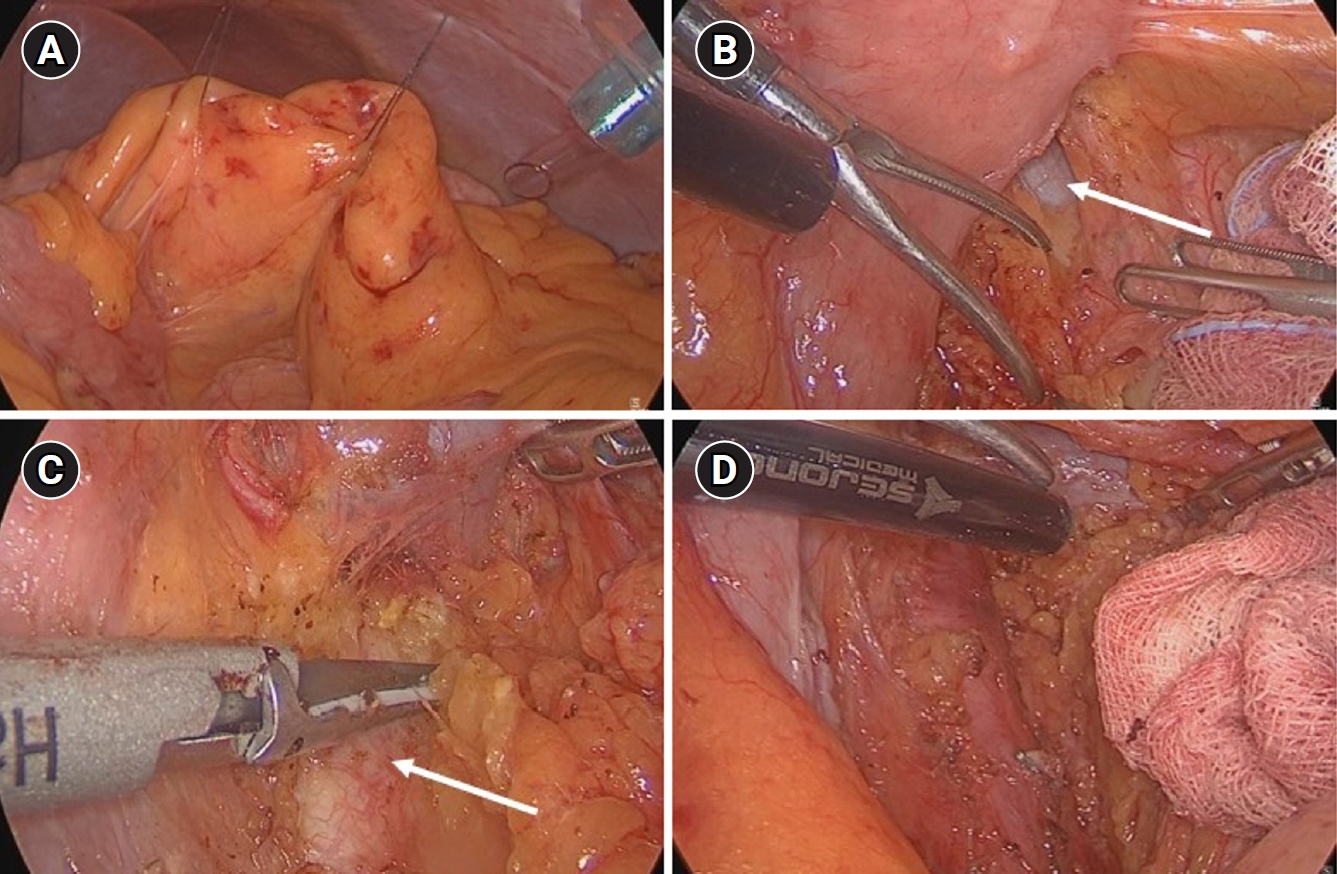

Given these findings, total gastrectomy with colon interposition and laparoscopic left PALN sampling were performed. The PALN was accessed by first identifying the ligament of Treitz, and then fixating the small bowel mesentery to the abdominal wall using a tagging suture for enhanced visualization of the target lymph node (Fig. 2A). This maneuver allowed easier identification of the left renal vein (Fig. 2B) and abdominal aorta (Fig. 2C), which enabled safe dissection and successful sampling of the PALN (Fig. 2D). Pathological evaluation confirmed the absence of metastasis, and a follow-up CT performed 4 months postoperatively showed complete resolution of the previously enlarged PALN (Fig. 1C).

(A) Small bowel mesentery tagging suture to ensure a stable view. (B) Left renal vein (arrow) checked in the left area of the ligament of Treitz. (C) Abdominal aorta (arrow) checked in the lower area of left renal vein. (D) After careful dissection in the left side of abdominal aorta and below the left renal vein, left paraaortic lymph node sampling was successful.

Case 2

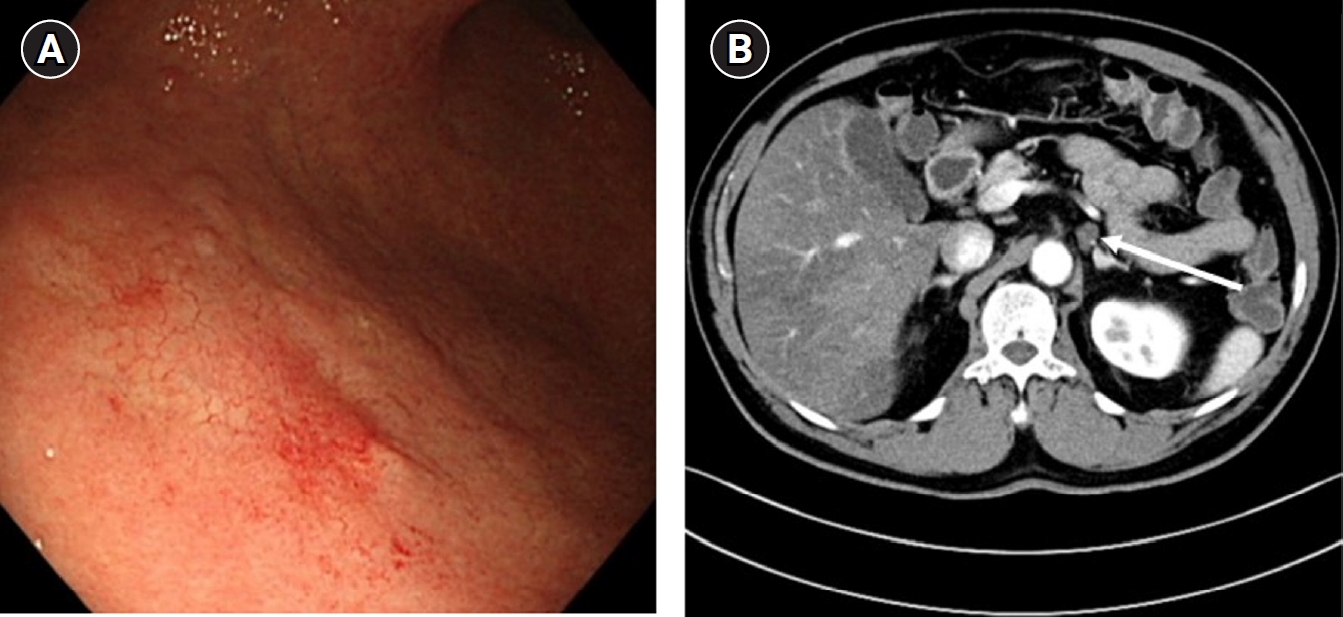

A 66-year-old male underwent EGD as part of a routine health screening, which revealed early gastric cancer located in the lower body and greater curvature of the stomach (Fig. 3A). Endoscopic submucosal dissection was performed, and pathological analysis indicated a 3.1×2.5 cm submucosal invasion (SM2; 640 μm from the muscularis mucosae). CT showed an indeterminate enlargement of the left PALN (Fig. 3B). No additional diagnostic studies, such as positron emission tomography-CT or multidisciplinary consultation, were undertaken. Although the likelihood of distant lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer is extremely low, a benign nature of the enlarged PALN could not be definitively excluded without histological confirmation. Consequently, a totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with gastrojejunostomy and left PALN sampling were performed.

(A) Esophagogastroduodenoscopy diagnosed with early gastric cancer on lower body and greater curvature. (B) During preoperative evaluation, left paraaortic lymph node enlargement was found just below splenic vein on computed tomography (arrow).

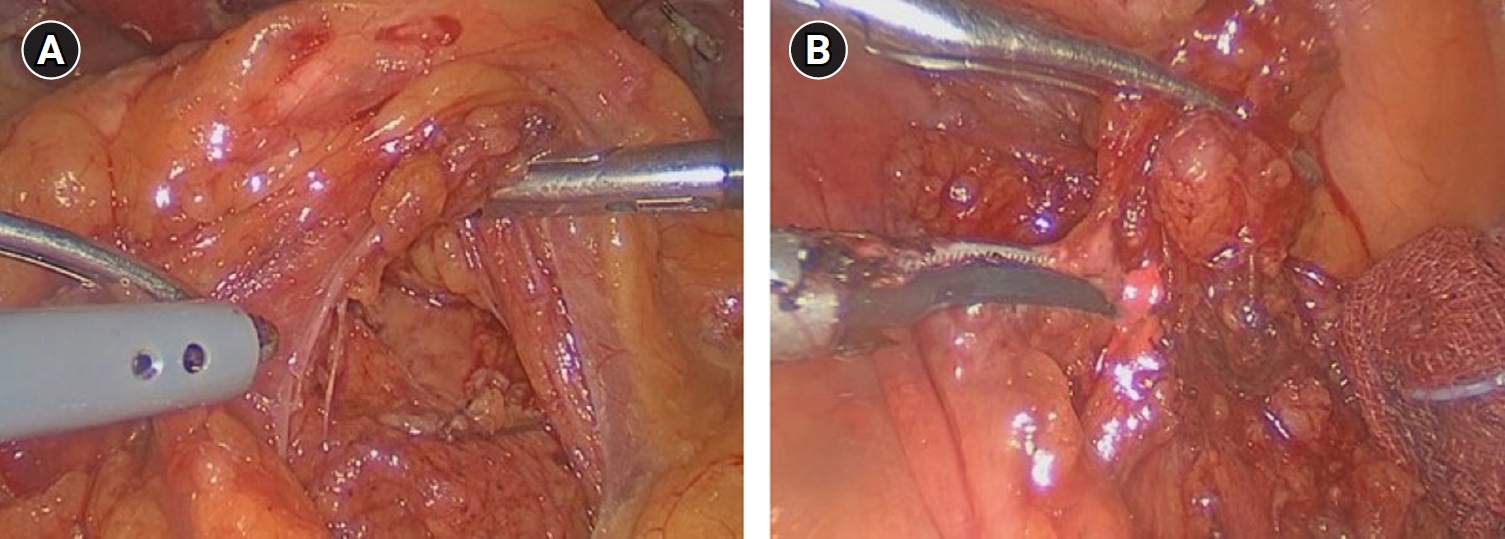

Preoperative CT localized the left PALN adjacent to the celiac trunk and inferior to the splenic vein. Initial dissection beneath the pancreas, following its elevation, failed to locate the lymph node (Fig. 4A). Subsequently, using the approach described above in Case 1, left PALN was successfully sampled and sent to the pathologist for confirmation (Fig. 4B). Pathological examination confirmed the tissue as ganglion, and the final diagnosis was stage I gastric cancer.

(A) Initially pancreas was lifted and then dissection was attempted, but enlarged paraaortic lymph node was not found. (B) Subsequently after approaching the ligament of Treitz, laparoscopic paraaortic lymph node sampling was successful.

With regard to the case reports described above, an exemption from review was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center.

Discussion

Lymph node metastasis is a critical prognostic factor in gastric cancer, necessitating adequate lymph node dissection during gastrectomy [5,6]. The standard approach for locally advanced gastric cancer is D2 lymphadenectomy [1].

The efficacy of paraaortic lymph node dissection (PALND) has been explored extensively. A landmark study conducted by the Japan Clinical Oncology Group and published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2008 demonstrated that prophylactic PALND does not improve survival outcomes in patients with resectable gastric cancer [7]. However, subsequent studies have suggested that in cases of locally advanced gastric cancer with extensive lymph node metastasis, PALND combined with D2 lymphadenectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy may confer survival benefits in selected patient populations [8,9]. While prophylactic PALND is generally not advantageous, the procedure remains a valuable diagnostic tool in certain cases.

When deemed necessary, performing PALN sampling for diagnostic purposes can provide essential information for accurate staging and personalized treatment planning. This is particularly important in cases of early gastric cancer where PALN enlargement is detected, as the treatment strategy differs significantly depending on whether the enlargement represents metastatic disease. Although distant lymph node metastasis is very rare in early gastric cancer, failure to confirm the benign of an enlarged PALN through biopsy may lead to challenges in clinical decision-making, including the potential overuse of adjuvant chemotherapy. PALN sampling enables definitive diagnosis and facilitates an evidence-based approach to subsequent treatment.

Laparoscopic PALN sampling is technically challenging due to limited accessibility and the proximity of major vascular structures such as the abdominal aorta and renal vein. Based on our clinical experience, several strategies can enhance the feasibility of this procedure. First, because most PALN enlargements are located near the ligament of Treitz, the laparoscopic port configuration mirrors the standard five-port setup used for laparoscopic gastrectomy. Second, considering the design and precision of the tip among various laparoscopic energy devices, the harmonic scalpel, with its capability for refined dissection, may offer advantages in achieving successful PALN sampling. Third, in our cases, all PALN enlargements were located on the left, obviating the need for alternative approaches such as the Kocher maneuver. Instead, sampling was successfully performed through the ligament of Treitz in all cases. And to achieve optimal visualization, the first assistant can elevate the small bowel using atraumatic graspers to stabilize the ligament of Treitz view. In patients with significant visceral adiposity, securing the small bowel mesentery to the abdominal wall with a tagging suture (e.g., black silk 3-0 or vicryl 3-0) in a vertical orientation greatly enhances visibility. This technique facilitates precise dissection in a stable operative field.

In conclusion, laparoscopic PALN sampling provides crucial diagnostic information for patients with enlarged PALN and should be performed only after good visualization and enough working space have been secured around the ligament of Treitz.

Notes

Disclosure

In-Seob Lee is an editor-in-chief and Sa-Hong Min is an associate editor of the journal, but they were not involved in the evaluation or decision-making process for this article and adhered to the decision made by independent reviewers. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: BOS, BSK; Supervision: SHM, ISL, MWY, JHY; Writing–original draft: BOS, JNY, BSK; Writing–review & editing: CSK, CSG, ISL, MWY, JHY, BSK.