Robot-Assisted Surgery Training for Medical Students in Low-Resource Areas: A Study Protocol

Article information

Abstract

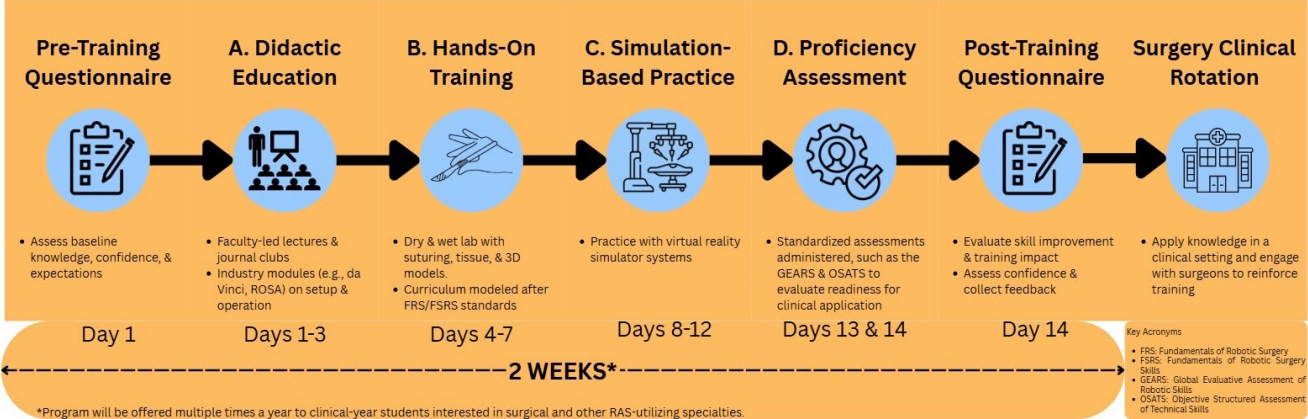

Robotic-assisted surgery (RAS), commonly associated with the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Inc.), has revolutionized minimally invasive surgery. As RAS systems are being increasingly adopted in teaching hospitals and used more frequently in procedures, there is a growing need for surgeons to be trained in this technology as early as the medical school years. In this article, we propose a potential low-resource, easily adoptable RAS pilot program that will be implemented at a medical school in Puerto Rico. A brief description of the program highlights faculty-led education, journal discussions, and simulation practice through hands-on modalities to establish early RAS proficiency in a feasible 2-week timeframe. By offering students early familiarity with robotic skills, this program may support specialty exploration and improve clinical preparedness. The goal of this pilot program proposal is not only to establish this protocol at a medical school in Puerto Rico but also to encourage other programs throughout the United States to consider adopting a similar training program in the hopes of making RAS training more ubiquitous in early medical training.

Introduction

Robotic-assisted surgery (RAS) has pioneered the field of minimally invasive surgery since the United States Food and Drug Administration approval of the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Inc.). Through three-dimensional (3D) image visualization and articulated instrumental control, this platform overcame many of the limitations of laparoscopic surgery [1]. As RAS implementation increases, there is a necessity to instruct future physicians to foster familiarity and foundational skills. As outlined in Fig. 1, we propose a potential 2-week pilot program to introduce medical students to RAS through didactics, lab practice, and simulator training.

San Juan Bautista School of Medicine Robotic Medical Student Training Program

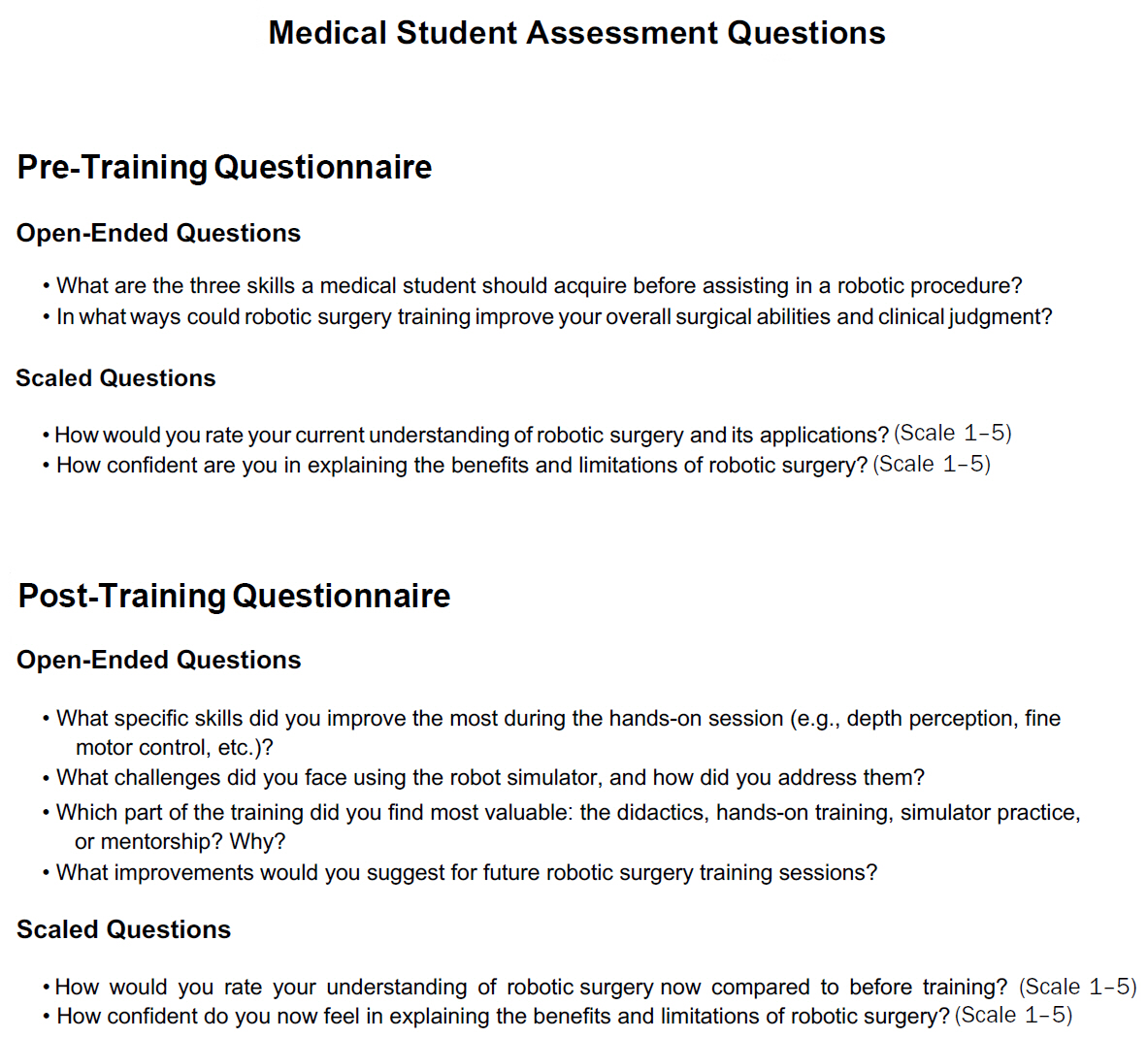

The proposed protocol is intended to take place before the 6-week surgery clinical rotation at San Juan Bautista School of Medicine, though 4th-year medical students who have completed the rotation may also participate. Student performance will be evaluated through a proficiency assessment as well as pre-/post-training questionnaires, as seen in Fig. 2.

Didactic education (days 1–3)

The didactic education phase focuses on introducing the background and fundamentals of robotics surgery through passive and active learning modalities brought to the students via faculty and industry manufacturers.

Faculty-sponsored

Faculty proficient in robotic surgery will provide lectures covering the history, current status, and prospects of robotic surgery. There will also be discussion of key published literature, educational videos, and evidence-based data on RAS across a broad spectrum of surgical disciplines in a ‘journal club’ format.

Hands-on training (days 4–7)

Following didactic education, students engage in hands-on training. This includes practice with suturing pads, animal tissue, and 3D printed organs. Programs such as the Fundamentals of Robotic Surgery (FRS) and the Fundamentals of Robotic Surgery Skills (FSRS) and the ‘fundamentals of robotic surgery skills’ further support this training with the incorporation of dry and wet lab components [1,3].

Simulation-based practice (days 8–12)

Virtual reality (VR) simulators play a crucial role in robotic surgery training, allowing students to practice and refine their skills in a controlled environment [1,3,4].

Proficiency assessment (days 13 & 14)

Proficiency is assessed using standardized tools, such as the Global Evaluative Assessment of Robotic Skills (GEARS) and the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS). These assessments will not be used as pass/fail evaluations but as tools to guide feedback and track progress. Cheng and Chao [5] emphasize the use of assessments such as GEARS as ‘standardized and validated’ for trainees to ‘reflect real surgical situations’. Ultimately, we aim to measure students’ skill acquisition using a formal framework, providing additional proctored practice for students needing more support [2].

Discussion

Since the da Vinci platform’s introduction in the late 1990s, RAS has expanded beyond traditional surgical fields into procedural specialties such as pulmonology and gastroenterology. Trials by Paez et al. [6] and Iacovazzo et al. [7] demonstrated that RAS, when used in bronchoscopy and gastrointestinal procedures, led to minimal side effects and quicker recovery compared to their respective gold standards without compromising procedure outcomes.

Unlike rigid prior programs, ours emphasizes flexibility and accessibility. Similar training programs like Mullens et al. [8] showed medical students gained procedural confidence after just 2 weeks. Our 2-week program will be offered to clinical-year medical students; in the case of San Juan Bautista, throughout the 3rd and 4th years. As many students are still undecided as to their specialty of choice when clinical years begin, this early exposure can clarify career goals, fill knowledge gaps, and enhance clinical and professional skills. Multiple offerings throughout the academic year will allow students to engage when it best supports their development.

Limitations include resource constraints, as RAS and simulators require substantial financial support for software updates, instrumentation, and education. The current state of healthcare in Puerto Rico is characterized by persistent structural challenges, which are exacerbated by recurrent natural disasters and economic instability [9]. Cultural/logistics barriers, faculty buy-in, and curriculum integration, may also impact implementation.

A 2023 study by Kalinov et al. [10] raised concerns about the limited availability of VR simulators and certified instructors. While access has improved, even in resource-limited regions like Puerto Rico, Kalinov et al. [10] state that VR training alone may fall short in developing fine motor tasks, such as camera targeting and threading, due to the dexterity required by the RAS. This reinforces the importance of hands-on skill development as a critical component of this program.

The cost is the most evident drawback of such a pilot program as hardware, software, maintenance, and consumables expenses can vary. However, many widely adopted platforms, such as da Vinci Xi and SP, arrive with integrated training packages that include online modules, VR simulators, dry labs, and certification programs. Specifically in its implementation in Puerto Rico, the equipment is government-funded in the county hospital of San Juan for clinical use and is also being used in academic hospital settings to train medical students, residents, and fellows. This infrastructure, combined with the medical school wet labs, facilitates a cost-effective implementation and sustainability at the medical school level.

As this manuscript presents a study protocol that has not yet been implemented, we have not included outcome measures or a sample-size calculation. Once approved by San Juan Bautista School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board and a pilot cohort of students is enrolled, we plan to measure percentage improvement in GEARS and learner confidence scores from pre- to post-assessment to support our determination of the sample-size for future implementations of the pilot program.

Conclusion

This proposed pilot protocol for a medical school in Puerto Rico provides a structured approach in robotic surgery, balancing knowledge with practical skills and clinical experience over a 2-week period. The curriculum is designed to be adaptable based on institutional resources and demonstrates that even with limited means, students can have early exposure to RAS, supporting early skill development and aligning with the dynamic demands of surgical education.

Notes

Disclosure

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: PFE; Methodology: IK, JJ, JM, PFE; Project administration: IK; Visualization: IK; Writing–original draft: IK, JJ, JM, PFE; Writing–review & editing: IK, JJ, JM, PFE.